The article addresses an important issue in the history of our country and people. This matter necessitates a more profound examination of our national historical and cultural origins in Western Azerbaijan, which currently constitutes part of Armenia. A comprehensive study of our history and culture beyond the present national boundaries holds significant relevance in the current phase. This work needs to be conducted meticulously across all historical periods, especially critical junctures.

The current turning point is influenced by the global shifts in the world order that occur over time. Throughout natural and historical processes, the established global order disintegrates and restructures to accommodate new realities. Within each emerging world order, a state's position, status, reputation, and potential hinge on various essential attributes. The late XX - early XXI centuries represent such a pivotal moment in history, not only for the entire world but also for nations that have regained their independence.

Azerbaijan in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, as a Turkic nation of Muslim origin, effectively asserts its ownership of land, heritage, history, and culture. It secures its rights on a global scale and rightfully claims its place in the international arena.

Present-day challenges for Azerbaijan are intrinsically tied to losses incurred during preceding centuries. In the late XVIII century, Azerbaijan faced feudal fragmentation, resulting in the splintering of the country into smaller khanates. By the early XIX century, weakened by internal conflicts, the region was invaded and divided by neighboring empires. Consequently, foreign settlers were established on its territories. This process notably included the resettlement of Armenians in Azerbaijani regions. Russian imperial authorities mainly dispatched Armenian settlers to the Karabakh, Iravan, and Nakhichevan khanates. This strategy aimed to weaken Ottoman Turkey's influence on the Turkic realm in the South Caucasus and Central Asia.

Notably, these objectives persist to the present day.

During the restoration of independence in 1918, the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic had an opportunity to assert sovereignty within its borders. However, lasting only 23 months, it couldn't fulfill its central mission of unifying its lands and claiming its national heritage, history, and culture.

Following the downfall of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, the Bolsheviks, who seized power, perpetuated imperial policies in a new form. The Armenian factor remained influential in this policy, similar to the past. The Soviet government and the Communist Party, under the pretext of slogans like proletarian internationalism and ethnic harmony, continued discriminatory and antagonistic actions against non-Christian nations, including the Azerbaijani people. Throughout the Soviet era, a continuous process of transferring Azerbaijani lands to Armenia, displacing Azerbaijanis from Armenia, and resettling Armenians from foreign countries took place.

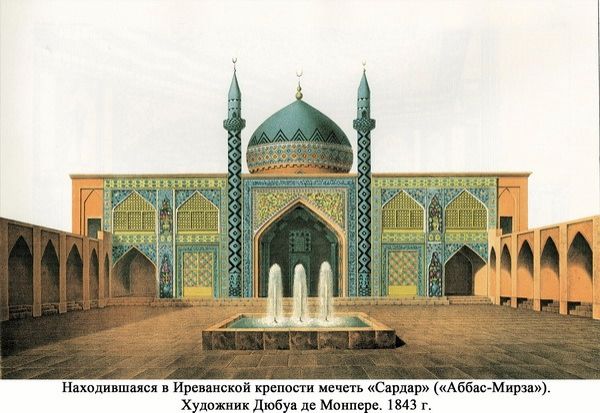

Concurrently, in Western Azerbaijan, now part of Armenia, destruction and Armenianization of monuments occurred, with toponyms altered to erase the national roots of the Azerbaijani people and obliterate their cultural legacy. Soviet authorities not only allowed these unlawful actions but also facilitated them. The systematic policy of eradicating the history and culture of the Turkic-Muslim population of the South Caucasus transpired under the direction of the party and government.

The utilization of the Armenian factor in Russia's colonial policy across different periods, both in the Russian Empire era and the Soviet period, played a central role in sustaining imperial dominance in the region. The policy of contemporary Russia toward its previous and current territories, as well as their populations, exhibits similarities with earlier eras.

In the early XVIII and XIX centuries, the Russian Empire's expansion into the South Caucasus prompted a multifaceted approach to solidify its authority in the region, influencing various aspects of public life. To establish imperial footholds within a region predominantly Turkic and Muslim, local Christians were instrumentalized. Among these, Christian Armenians, historically residing in Muslim lands, were favored. The Armenians were perceived as capable of serving the empire's interests due to their willingness to betray their neighbors. This approach persisted from the early 18th century, with Peter I acknowledging this trait among Armenians and suggesting its utilization in occupying the South Caucasus.

By the early XIX century, as Russia entered and occupied the South Caucasus, the strategy of deploying the Armenian factor, a component of Russia's aggressive policy, escalated. Notably, a significant portion of the compensation received from Iran under the Turkmenchay Treaty was allocated to settle Armenians in the region. Armenians were given fertile lands, tax exemptions, and substantial representation in the imperial administration. These privileges remained in effect through the Russian Empire and Soviet Union eras, further intensifying the policy.

Throughout its presence in the region, Russia safeguarded its interests in the South Caucasus, using its policies to serve these interests. Apart from populating the region with Armenians to consolidate imperial control, this strategy aimed to curb relations between the Ottoman state and the Turkic world. Erasing the Turkic-Muslim roots and obstructing Turkic unity served imperial interests. Thus, Russia facilitated Armenians' activities that distorted and falsified Turkic-Muslim cultural heritage in the South Caucasus.

A crucial factor bolstering Armenian establishment in the region was the transfer of the material and spiritual legacy of the Albanian Catholic Church to the Armenian-Gregorian Church in 1836. This transfer provided the Armenians, who previously had limited presence in the South Caucasus, a potent instrument. Colonial Russia orchestrated the falsification of the thousand-year history of the Albanian Church, armenianized religious monuments, and fabricated Armenian legends.

During this period, the construction of the first Armenian churches in the South Caucasus occurred. Albanian churches underwent external and internal transformations to be presented as Armenian.

Falsification and armenianization of written sources related to Azerbaijan and its Albanian history transpired after the 1830s. Many alleged "Armenian sources" supposedly from various eras were either falsifications of Albanian sources or falsely attributed to ancient times. The history of "khachkar" stone slabs, considered Armenian, doesn't extend beyond the 19th and 20th centuries. These stones were predominantly created later, particularly in the 20th and 21st centuries, and placed where Armenians could access them in the South Caucasus. They were then presented as concrete evidence of historical roots.

In the areas where Armenians settled, their primary duty to the Russian Empire was to gather and relay information about the Turkic-Muslim population to the authorities, reporting any movements that could jeopardize the empire's stability. In exchange, they received substantial rewards and enjoyed considerable freedom. They could even alter place and settlement names at will.

While these practices persisted for some time, the changing geopolitical landscape has left these individuals seeking a new patron. The former protector, Russia, unable to satisfy Armenians' growing ambitions due to global shifts, no longer suffices. Consequently, Armenians are now aspiring to find new benefactors who align with their old ideology. The Armenian people find themselves ensnared by their "leaders'" policies.

Times have evolved, and clinging to fabricated legends and adventurous ideals, fostering enmity with neighbors, and isolating themselves will impede the Armenians from escaping the quagmire of hatred and achieving normal social and economic progress. Recognizing this reality sooner will enable them to embark on a path of advancement.

Author: Ibrahim Aliyev

Historian scholar