A telescope in Chile has traced the distribution of this mysterious stuff on a quarter of the sky and across almost 14 billion years of time.The result is once again a spectacular confirmation of Einstein's ideas.Although dark matter makes up about 85% of all mass in the Universe, it's extremely difficult to detect and defies a ready description.

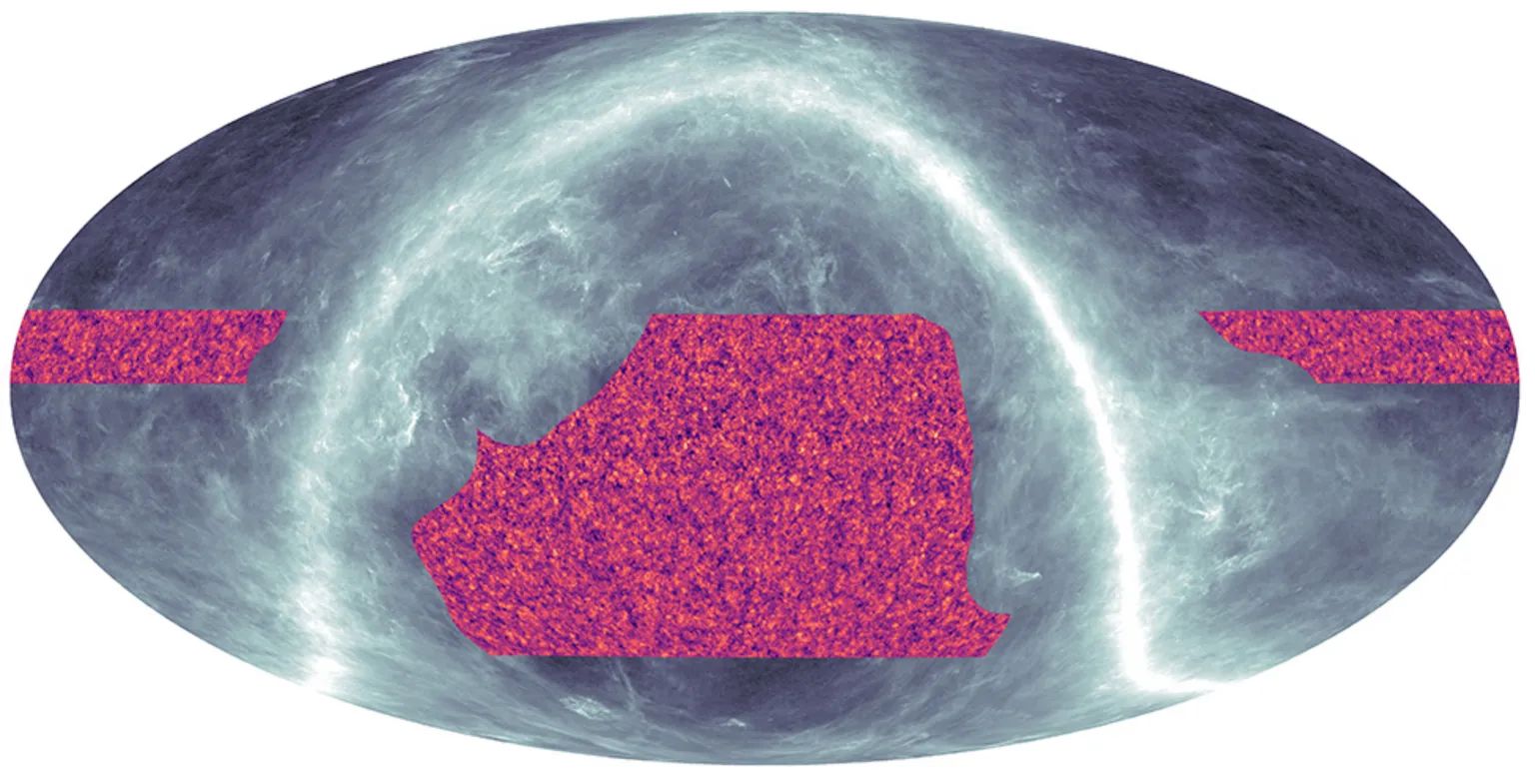

But dark matter influences the large scale structure of everything we see - where all the galaxies are, where the voids in space are. It's the scaffolding on which the visible structure of the Universe is hung.In the image at the top of this page, the coloured areas are the portions of the sky studied by the telescope.Orange regions show where there is more mass, or matter, along the line of sight; purple where there is less. Typical features are hundreds of millions of light-years across.

White areas show where contaminating light from dust in our Milky Way galaxy has obscured a deeper view.The distribution of matter agrees very well with scientific predictions.ACT observations indicate that the "lumpiness" of the Universe and the rate at which it has been expanding after 14 billion years of evolution are just what you'd expect from the standard model of cosmology, which has Einstein's theory of gravity (general relativity) at its foundation.

Recent measurements that used an alternative background light, one emitted from stars in galaxies rather than the CMB, had suggested the Universe lacked sufficient lumpiness. Prof Blake Sherwin from Cambridge University.Planck and several other probes are coming in on the lower side. Obviously, you could have a scenario where both the measurements are right and there's some new physics that explains the discrepancy.But we're using independent techniques, and I think we're now starting to close the loophole where we could all be riding this new physics and one of the measurements has to be wrong.

Papers describing the new results have been submitted to The Astrophysical Journal and posted.The telescope, which worked from 2007 to 2022 before being dismantled, was funded by the US National Science Foundation. The scientific collaboration has yet to finish analysing all its data.When Planck looked at temperature fluctuations across the CMB, it determined the rate to be about 67 kilometres per second per megaparsec.

Or put another way - the expansion increases by 67km per second for every 3.26 million light-years we look further out into space.A tension arises because measurements of the expansion in the nearby Universe, made using the recession from us of variable stars, clocks in at about 73km/s per megaparsec.

Madina Mammadova\\EDnews