Politicians and experts have long been expressing concerns regarding the situation on the Afghan side of the border near Tajikistan. The length of the border the two countries share is 1,344km, of which 920km are the Gorno-Badakhshan section while the remaining over 424km are the Khatlon Region of Tajikistan. The latter section is the one that causes most concern in terms of attempts to violate the state border from the Afghan side to contraband illicit drugs. The situation in the southern ends of Gorno-Badakhsan Autonomous Region, known by is Russian abbreviation, GBAO, is relative stable. However, according to experts, there is a risk that the situation could deteriorate.

Tense silence

The residents of Gorno-Badakhshan believe that everything is calm in the border zones. Many villages in GBAO are located very close to the border with Afghanistan and the residents of both sides can see and watch each other without even binoculars.

“The Afghan villages are located along the Panj River, just like our villages. They are so close we can see what is happening on the other side. This is a very close relative nation. Just like us, they are busy with their problems. They have a patriarchal mode of society. They are engaged in agriculture—they sow, plant and harvest crops. They, too, have a lot of fruits—like we do. They now have electricity on the other side: they watch TV and have satellite dishes. They recently built a road; just flat and dirt, but of good quality. It is being built by the local resident along the river just like the road on the Tajik side. Each village is building its portion of the road on its territory—starting from Ishkashim all the way to the Tajik village of Zigar,” says Payshambe from the village of Porshnev in Badakhshan.

The village of Nusay in the Afghan side of Badakhshan across from the Tajik village of Darvaz

“I have been driving on the Dushanbe-Khorog route for 16 to 17 years, and nobody fired a shot on the other side and we have not seen any armed men,” driver Sharif says. “Willingly or not, we always watch what’s happening on the other side while driving by—they have cars there as well now. We have been living next to each other for so many years, and not even a single threat against us arose from Afghanistan.

“If there is a violation of borders somewhere, local residents would learn instantaneously. That is how things go in Pamir. News spread very quickly here, that is why everyone knows everything about everyone else. Therefore, I can confidently say if there are any violations, then those are isolate incidents, not massive cases. Hence, the trafficking of drugs is insignificant as well. It is no secret that those who are engaged in this criminal activity, transporting [drugs] via Pamir is a very expensive luxury, which resulted in shifting drug trafficking routes toward southern parts of the Tajik-Afghan border,” argues Sobir, a Rushan resident.

Agha Khan Foundation for development and other international agencies are closely engaged on the Afghan side of Badakhshan as well as the Tajik energy company called Pamir Energy. These organisations cover a population of some 800,000 people.

The Agha Khan Foundation has built five bridges over Panj since 2002; the bridges link villages in Tajikistan and Afghanistan and are used for delivering humanitarian aid from Tajikistan into Afghanistan. Border town bazaars take place once a week near the bridges. Residents on both sides of the river sell simple household stuff and staples, Tajik businessman Salim says.

A bridge in village of Tem and administrative buildings

Experts concerned

But somewhat different picture emerges on the other side of Panj. Mir Ali, a resident of the Sultoni Ishkoshim village, told Fergana that there between 100 and 150 militants from the Afghan Taliban and mercenaries from the CIS and China—ethnic Kyrgyz, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Chechens and Uighurs—in Varduj. According to Najib, a resident of another Afghan village of Viyod, such accumulation of Taliban and international extremist groups is a seasonal occurrence.

“They have nothing to do in winter and nobody provides them [with food, etc.], so in spring they gather in this province in numbers ranging from 1,000 to 2,000 individuals,” Najib maintains.

Omar Nessar, Director of Centre for Studying Modern Afghanistan, believes the relative calm in the Afghan part of Badakhshan is a temporary phenomenon:

“The very fact that militants have been controlling several districts in the Afghan part of Badakhshan for quite a long time forces us to be on guard at all times. According to Afghan mass media, the number of militants is increasing in the areas they control, partially thanks to incoming foreign mujahedeen. One can only guess what goals they are pursuing and when they will start acting. However, it seems to me that one must not concentrate attention on Badakhshan only. The Tajik part of Badakhshan is protected by its natural setting, which makes an illegal border crossing difficult there. That said, the Kunduz and Takhar areas do not have such natural boundaries,” Mr Nessar emphasises.

Khursand Khurramov, a political scientist in Tajikistan, says not only the Taliban, but also groups affiliated with IS pose a threat of destabilising the situation in southern parts of Tajikistan.

“The last time the Taliban movement was active in northern Afghanistan, in Kunduz Province that is, was observed in October 2016. However, not the Taliban but small groups sympathising with IS, which have a number of nationals of post-Soviet countries, are a more potential danger as far as southern parts of Tajikistan are concerned. Hypothetically, these groups could pose danger primarily to Ismaili Shi’as, who life on both banks of Panj in Badakhshan, should circumstances deteriorate to a dangerous level. However, in reality, they are dispersed at this time and do not possess enough might to be able to withstand an army or cross the border. Moreover, they are potential enemies of the Taliban within Afghanistan itself.

At this time, the situation on the borders, especially in the Badakhshan parts of it, is calm. But until there is a political consensus among the Afghan elites, the government cannot control the situation; hence, the threat of deterioration of the situation on the Afghan-Tajik border remains quite potent. Given the current conditions, it is extremely important for Tajikistan to maintain internal political stability in Afghanistan. In case of another political crisis breaks out, a flow of refugees may burst into Tajikistan and with them various extremist elements could enter. This entails [dangers], because there are certain [presumably: supportive] attitudes and sympathies inside Tajikistan already toward some of the destructive groups,” Mr Khurramov maintains.

The Moy May village on the Afghan bank of the Panj River

Alim Sherzamonov, a political scientist and social activist in Tajikistan, is certain that IS fighters will not be able to settle in Afghanistan or establish serious organisational structures for that matter. The Taliban already are conflicting with the Afghan government, and are not intending to expand their influence beyond the boundaries of Afghanistan:

“There are territories under the Taliban control in Badakshan as well. But there are no IS fighters on the other side. Whereas groups of foreign mercenaries from Central Asia and North Caucasus, who are a source of concern for regional leaders—China and Russia, that is—are based precisely in those territories, which the Taliban control. The IS will not be able establish itself there because it is a supranational union striving to be a globally dominant power. Meanwhile, Taliban is an exclusively Afghan phenomenon and exclusively Pashto ethnic movement, who pursue domestic policies and not regional or global dominance. In other words, the latter do not intend to capture foreign territories. They have not transformed over the many years [of their existence] and they are not turning into a supranational movement. And that has not happened even when they held political power.

“Looking at [Northern] Afghanistan, one can conclude that the Taliban are still exerting influence on certain parts of the country, but there are no more strong resistances between the government and the Taliban in the form of daily battles. Apparently, armed conflicts take place when the parties violate some fragile balance in certain locales, or the Taliban want to exercise influence on certain decisions the government adopts, including those that have to do with official position appointments. The same applies to border zones,” Mr Sherzamonov concludes.

Everything is calm on the Tajik bank of the Panj River at this time. Fergana’s own photographer-reporter has made these photographs in December 2016.

An administrative building near a bridge in the Chormarchi Bolo village in Afghanistan

Two extreme roads on the two banks of Panj

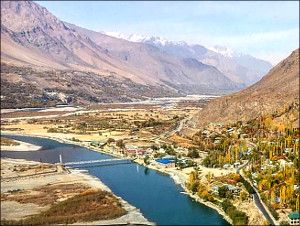

An aerial view on the Panj River

A bridge linking the two banks: Vanch, Tajikistan and Chomarchi Bolo, Afghanistan

The border in unhindered view

Afghanistan on the left, Tajikistan on the right