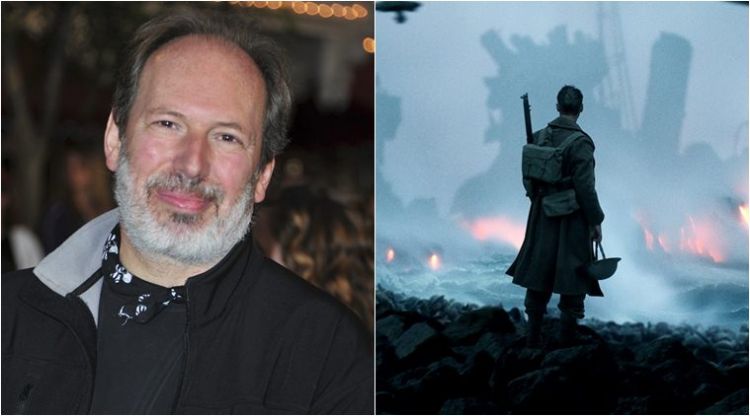

Hans Zimmer and Christopher Nolan are one of the most famous director-composer duos in the history of cinema. They share a rapport similar to Steven Spielberg and John Williams. The bond between Nolan and Zimmer seems even closer. The British director trusts the German composer blindly. He gave him the job to score the main theme of his film Interstellar but did not tell him that. Instead, he just said that the piece of music was supposed to be an instrumental of the relationship between a father and son, who got estranged. Zimmer did that and we know that piece of music as “Stay”.

Whenever Nolan and Zimmer decide to work together (which is always when Nolan is making a film), you can expect great things. Nolan’s films are full of groundbreaking ideas and subversive themes, and they need a soundtrack to match. Here is where Hans Zimmer comes in. Every Nolan film has a dominant theme of time. Right from Following to Memento to Dunkirk, it is one of this auteur’s principal pleasures to play with time as a concept. And Zimmer knows that, having worked with him from Batman Begins. In Dunkirk, Nolan’s triptych, there is precious little dialogue, and that is why the score of the film is more scrutinised than is usual.

The film soundtrack is not as independently listenable as other Zimmer soundtracks. It is specifically written for the film and due to the intensity of the scenes, it is often harsh and too loud. If you watched the film in an IMAX, you would know what I am talking about. Remember that ticking sound from the trailer that sounds like it came from a pocket watch but was unbelievably intense? Well, this is exactly how the deadly duo came up with it. “Very early on I sent Hans a recording that I made of a watch that I own, with a particularly insistent ticking, and we started to build the track out of that sound. And then working from that sound, we built the music as we built the picture cut,” Nolan told Business Insider.

Right from the beginning, the score is mostly a crescendo, rising and rising and eventually settling. Actually, it does not rise. Nolan and Zimmer use Shepard tone, a technique that makes a piece of music seem increasing in intensity, but it is, in reality, an auditory illusion. “The Mole”, the opening cue of Dunkirk, is almost scary as it has that foreboding feel that is usually found in horror movies. The music gets only acuter. In “We Need Our Army Back”, there is a sense of hopelessness.

As the film proceeds, the mood of the score changes from ominous to downright infernal (and deafeningly loud) when German dive-bombers are raining hellfire on British soldiers. As the evacuation begins in earnest with civilians pitching in, there is a mellowing down and a subtle shift in the score. This is masterful work. Dunkirk is certainly not the best work of Zimmer, but it does come close.